8 Mosaic Of Subcultures**

|

. . . the most basic structure of a city is given by the relation of urban land to open country - City Country Fingers (3). Within the swaths of urban land the most important structure must come from the great variety of human groups and subcultures which can co-exist there.

Compare three possible alternative ways in which people may be distributed throughout the city: 1. In the heterogeneous city, people are mixed together, irrespective of their life style or culture. This seems rich. Actually it dampens all significant variety, arrests most of the possibilities for differentiation, and encourages conformity. It tends to reduce all life styles to a common denominator. What appears heterogeneous turns out to be homogeneous and dull.

2. In a city made up of ghettos, people have the support of the most basic and banal forms of differentiation - race or economic status. The ghettos are still homogeneous internally, and do not allow a significant variety of life styles to emerge. People in the ghetto are usually forced to live there, isolated from the rest of society, unable to evolve their way of life, and often intolerant of ways of life different from their own.

3. In a city made of a large number of subcultures relatively small in size, each occupying an identifiable place and separated from other subcultures by a boundary of nonresidential land, new ways of life can develop. People can choose the kind of subculture they wish to live in, and can still experience many ways of life different from their own. Since each environment fosters mutual support and a strong sense of shared values, individuals can grow.

This pattern for a mosaic of subcultures was originally proposed by Frank Hendricks. His latest paper dealing with it is "Concepts of environrnental quality standards based on life styles," with Malcolm MacNair (Pittsburg, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh, February 1969). The psychological needs which underlie this pattern and which make it necessary for subcultures to be spatially separated in order to thrive have been described by Christopher Alexander, "Mosaic of Subcultures," Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, 1968. The following statement is an excerpt from that paper.

I.

|

We are the hollow men. . . . -T. S. Eliot |

Many of the people who live in metropolitan areas have a weak character. In fact, metropolitan areas seem almost marked by the fact that the people in them have markedly weak character, compared with the character which develops in simpler and more rugged situations. This weakness of character is the counterpart of another, far more visible feature of metropolitan areas: the homogeneity and lack of variety among the people who live there. Of course, weakness of character and lack of variety, are simply two sides of the same coin: a condition in which people have relatively undifferentiated selves. Character can only occur in a self which is strongly differentiated and whole: by definition, a society where people are relatively homogeneous, is one where individual selves are not strongly differentiated.

Let us begin with the problem of variety. The idea of men as millions of faceless nameless cogs pervades 20th century literature. The nature of modern housing reflects this image and sustains it. The vast majority of housing built today has the touch of mass-production. Adjacent apartments are identical. Adjacent houses are identical. The most devastating image of all was a photograph published in Life magazine several years ago as an advertisement for a timber company: The photograph showed a huge roomful of people; all of them had exactly the same face. The caption underneath explained: In honor of the chairman's birthday, the shareholders of the corporation are wearing masks made from his face.

These are no more than images and indications.... But where do all the frightening images of sameness, human digits, and human cogs, come from? Why have Kafka and Camus and Sartre spoken to our hearts?

Many writers have answered this question in detail - [David Riesman in The Lonely Crowd; Kurt Goldstein in The Organism; Max Wertheimer in The Story of Three Days; Abraham Maslow in Motivation and Personality; Rollo May in Man's Search for Himself, etc.] . Their answers all converge on the following essential point: Although a person may have a different mixture of attributes from his neighbour, he is not truly different, until he has a strong center, until his uniqueness is integrated and forceful. At present, in metropolitan areas, this seems not to be the case. Different though they are in detail, people are forever leaning on one another, trying to be whatever will not displease the others, afraid of being themselves.

People do things a certain way "because that's the way to get them done" instead of "because we believe them right." Compromise, going along with the others, the spirit of committees and all that it implies - in metropolitan areas, these characteristics have been made to appear adult, mature, well-adjusted. But euphemisms do little to disguise the fact that people who do things because that's the way to get along with others, instead of doing what they believe in, do it because it avoids coming to terms with their own self, and standing on it, and confronting others with it. It is easy to defend this weakness of character on the grounds of expediency. But however many excuses are made for it, in the end weakness of character destroys a person; no one weak in character can love himself. The self-hate that it creates is not a condition in which a person can become whole.

By contrast, the person who becomes whole, states his own nature, visibly, and outwardly, loud and clear, for everyone to see. He is not afraid of his own self; he stands up for what he is; he is himself, proud of himself, recognizing his shortcomings, trying to change them, but still proud of himself and glad to be himself.

But it is hard to allow that you which lurks beneath the surface to come out and show itself. It is so much easier to live according to the ideas of life which have been laid down by others, to bend your true self to the wheel of custom, to hide yourself in demands which are not yours, and which do not leave you full.

It seems clear, then, that variety, character, and finding your own self, are closely interwoven. In a society where a man can find his own self, there will be ample variety of character, and character will be strong. In a society where people have trouble finding their own selves, people will seem homogeneous, there will be less variety, and character will be weak.

If it is true that character is weak in metropolitan areas today, and we want to do something about it, the first thing we must do, is to understand how the metropolis has this effect.

II.

How does a metropolis create conditions in which people find it hard to find themselves?

We know that the individual forms his own self out of the values, habits and beliefs, and attitudes which his society presents him with. [George Herbert Mead, Mind, Self and Society.] In a metropolis the individual is confronted by a vast tableau of different values, habits and beliefs and attitudes. Whereas, in a primitive society, he had merely to integrate the traditional beliefs (in a sense, there was a self already there for the asking), in modern society each person has literally to fabricate a self, for himself, out of the chaos of values which surrounds him.

If, every day you do something, you meet someone with a slightly different background, and each of these peoples' response to what you do is different even when your actions are the same, the situation becomes more and more confusing. The possibility that you can become secure and strong in yourself, certain of what you are, and certain of what you are doing, goes down radically. Faced constantly with an unpredictable changing social world, people no longer generate the strength to draw on themselves; they draw more and more on the approval of others; they look to see whether people are smiling when they say something, and if they are, they go on saying it, and if not, they shut up. In a world like that, it is very hard for anyone to establish any sort of inner strength.

Once we accept the idea that the formation of the self is a social process, it becomes clear that the formation of a strong social self depends on the strength of the surrounding social order. When attitudes, values, beliefs and habits are highly diffuse and mixed up as they are in a metropolis, it is almost inevitable that the person who grows up in these conditions will be diffuse and mixed up too. Weak character is a direct product of the present metropolitan society.

This argument has been summarized in devastating terms by Margaret Mead [Culture, Change and Character Structure]. A number of writers have supported this view empirically: Hartshorne, H. and May, M. A., Studies in the Nature of Character, New York, Macmillan, 1929; and "A Summary of the Work of the Character Education Inquiry," Religious Education, 1930, Vol. 25, 607-619 and 754-762. "Contradictory demands made upon the child in the varied situations in which he is responsible to adults, not only prevent the organisation of a consistent character, but actually compel inconsistency as the price of peace and self-respect." . . .

But this is not the end of the story. So far we have seen how the diffusion of a metropolis creates weak character. But diffusion, when it becomes pronounced, creates a special kind of superficial uniformity. When many colors are mixed, in many tiny scrambled bits and pieces, the overall effect is grey. This greyness helps to create weak character in its own way.

In a society where there are many voices, and many values, people cling to those few things which they all have in common. Thus Margaret Mead (op. cit.): "There is a tendency to reduce all values to simple scales of dollars, school grades, or some other simple quantitative measure, whereby the extreme incommensurables of many different sets of cultural values can be easily, though superficially, reconciled." And Joseph T. Klapper [T:he Effects of Mass Communication, Free Press, 1960]:

"Mass society not only creates a confusing situation in which people find it hard to find themselves - it also . . . creates chaos, in which people are confronted by impossible variety - the variety becomes a slush, which then concentrates merely on the most obvious."

. . . It seems then, that the metropolis creates weak character in two almost opposite ways; first, because people are exposed to a chaos of values; second, because they cling to the superficial uniformity common to all these values. A nondescript mixture of values will tend to produce nondescript people.

III.

There are obviously many ways of solving the problem. Some of these solutions will be private. Others will involve a variety of social processes including, certainly, education, work, play, and family. I shall now describe one particular solution, which involves the large scale social organisation of the metropolis.

The solution is this. The metropolis must contain a large number of different subcultures, each one strongly articulated, with its own values sharply delineated, and sharply distinguished from the others. But though these subcultures must be sharp and distinct and separate, they must not be closed; they must be readily accessible to one another, so that a person can move easily from one to another, and can settle in the one which suits him best.

This solution is based on two assumptions:

I. A person will only be able to find his own self, and therefore to develop a strong character, if he is in a situation where he receives support for his idiosyncrasies from the people and values which surround him.

2. In order to find his own self, he also needs to live in a milieu where the possibility of many different value systems is explicitly recognized and honored. More specifically, he needs a great variety of choices, so that he is not misled about the nature of his own person, can see that there are many kinds of people, and can find those whose values and beliefs correspond most closely to his own.

. . . one mechanism which might underlie people's need for an ambient culture like their own: Maslow has pointed out that the process of self actualization can only start after other needs, like the need for food and love, and security, have already been satisfied. [Motivation and Personality, pp. 84-89.] Now the greater the mixture of kinds of persons in a local urban area, and the more unpredictable the strangers near your house, the more afraid and insecure you will become. In Los Angeles and New York this has reached the stage where people are constantly locking doors and windows, and where a mother does not feel safe sending her fifteen year old daughter to the corner mailbox. People are afraid when they are surrounded by the unfamiliar; the unfamiliar is dangerous. But so long as this fear is an unsolved problem, it will override the rest of their lives. Self-actualization will only be able to happen when this fear is overcome; and that in turn, can only happen, when people are in familiar territory, among people of their own kind, whose habits and ways they know, and whom they trust.

. . . However, if we encourage the appearance of distinct subcultures, in order to satisfy the demands of the first assumption, then we certainly do not want to encourage these subcultures to be tribal or closed. That would fly in the face of the very quality which makes the metropolis so attractive. It must be possible, therefore, for people to move easily from one subculture to another, and for them to choose whichever one is most to their taste; and they must be able to do all of this at any moment in their lives. Indeed, if it ever becomes necessary, the law must guarantee each person freedom of access to every subculture....

IV.

It seems clear, then, that the metropolis should contain a large number of mutually accessible subcultures. But why should those subcultures be separated in space. Someone with an a spatial bias could easily argue that these subcultures could, and should, coexist in the same space, since the essential links which create cultures are links between people.

I believe this view, if put forward, would be entirely wrong. I shall now present arguments to show that the articulation of subcultures is an ecological matter; that distinct subcultures will only survive, as distinct subcultures, if they are physically separated in space.

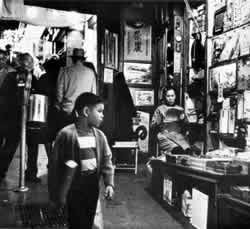

First, there is no doubt that people from different subcultures actually require different things of their environment. Hendricks has made this point clearly. People of different age groups, different interests, different emphasis on the family, different national background, need different kinds of houses, they need different sorts of outdoor environment round about their houses, and above all, they need different kinds of community services. These services can only become highly specialised, in the direction of a particular subculture, if they are sure of customers. They can only be sure of customers if customers of the same subculture live in strong concentrations. People who want to ride horses all need open riding; Germans who want to be able to buy German food may congregate together, as they do around German town, New York; old people may need parks to sit in, less traffic to contend with, nearby nursing services; bachelors may need quick snack food places; Armenians who want to go to the orthodox mass every morning will cluster around an Armenian church; street people collect around their stores and meeting places; people with many small children will be able to collect around local nurseries and open play space.

This makes it clear that different subcultures need their own activities, their own environments. But subcultures not only need to be concentrated in space to allow for the concentration of the necessary activities. They also need to be concentrated so that one subculture does not dilute the next: indeed, from this point of view they not only need to be internally concentrated - but also physically separated from one another....

We cut the quote short here. The rest of the original paper presents empirical evidence for the need to separate subcultures spatially, and in this-book - we consider that as part of another pattern. The argument is given, with empirical details, in SUBCULTURE ROUNDARY (13).

Therefore:

Do everything possible to enrich the cultures and subcultures of the city, by breaking the city, as far as possible, into a vast mosaic of small and different subcultures, each with its own spatial territory, and each with the power to create its own distinct life style. Make sure that the subcultures are small enough, so that each person has access to the full variety of life styles in the subcultures near his own.

We imagine that the smallest subcultures will be no bigger than 150 feet across; the largest perhaps as much as a quarter of a mile - Community of 7000 (12), Identifiable Neighborhood (4), House Cluster (37). To ensure that the life styles of each subculture can develop freely, uninhibited by those which are adjacent, it is essential to create substantial boundaries of nonresidential land between adjacent subcultures - Subculture Boundary (13). . . .

![]()

A Pattern Language is published by Oxford University Press, Copyright Christopher Alexander, 1977.